Two contradictory technological currents combine to further disempower the already disadvantaged.

Two contradictory technological currents combine to further disempower the already disadvantaged.

On one hand, the assumption that people in general have a certain technical capacity (both access and skills) means that those without that capacity are left on the wrong side of the digital divide pushing them into a downward spiral that mirrors the compounding impacts of economic disadvantage.

On the other hand, the concerns around privacy and individual control of their online profile are a luxury that only the rich can afford. If you are not securely and comfortably connected to the digital systems that underpin modern life, you do not get the right to be choosy about the manner in which your profile is built or managed.

Excluding the technologically disadvantaged

An example may help.

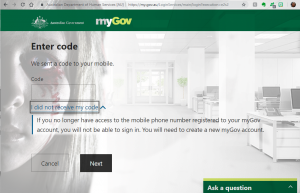

To log into any of the major government agencies – Taxation, Medicare, My Health, NDIS, Veteran Services as well as any of the welfare services on which millions of Australian depends – you must enter your username and password and then verify your identity by entering the code that arrives at your mobile phone. If you do not have a mobile phone you are advised that you cannot use the online services and you must go to an office of the relevant service.

Thus, the elderly, the digitally illiterate, those with a physical or mental characteristic that causes them to struggle with a smart phone are forced to physically attend offices while the rest of us blithely manage our health records or report our taxation figures online. In many cases, those offices present another range of barriers. At the Centrelink office, for example, you are encouraged to reduce the load on staff by using the computers at the side of the office to access your claim online.

So far, this example defines the relatively straightforward argument that we increasingly rely on services that demand a technological capacity that is not universally available. It is easy to understand that people with limited, flawed or no access to digital technology are at a disadvantage when it comes to engaging with certain aspects of modern life. While the scale of this disadvantage is not widely understood – partly because of its compound nature – the concept it easy to grasp.

Profiling them regardless

The second force at work, though, is more subtle. The privacy implications of digital technology are far reaching and complex. Consider the case of a person completely refusing to engage in the digital world, thereby maintaining their privacy by maintaining what is known in the business as an “air gap”.

Refusing to participate in the digital world certainly ensures complete protection from direct access to your activity, it does not guarantee that you do not have a digital footprint and it certainly does not allow you to manage or shape your digital profile.

Take the example of an elderly person who has no mobile phone or debit card.

Even though they do not participate in social media, for example, they still have a digital profile compiled from references to them made by their friends and relatives. Similarly, face recognition software that draws on databases of passport and license photos does not require their online engagement to store the photograph from their passport or driver’s license.

The My Health record is a recent and controversial example of an online database that requires every citizen to engage, even if it simply to state that you wish to disengage.

So, the complete refusal to engage is the simplest example of disengagement and it still involves complex ethical and practical considerations. If we consider those people who use debit cards for banking and mobile telephones to make calls and send text messages but otherwise resist engagement in the more advanced digital platforms the complexities multiply significantly.

The implications

Once we start to examine how much control someone has over the digital profile that they willingly create but wish to manage, the issues become so complex that we struggle to find the boundaries.

Consider a woman fleeing domestic violence, applying for help from the government to support her in a safe refuge form her violent partner.

The first thing that any domestic violence support organisation will do is remove the SIM card from her phone, cut it in half, smash the mobile phone to pieces and deposit the lot in a bin. The mobile phone is the most common mechanism whereby perpetrators of domestic violence track down their victims. The days following the departure from the scene of domestic violence represent the greatest danger to victims of violence. More women are killed attempting to flee domestic violence than enduring it, this is one of the major challenges for agencies attempting to support women who face violence in a relationship.

Now, because government departments insist that citizens have a mobile phone to gain online access to their own records, the next thing the agency has to do is to assist the woman to set up new telephone and email account so that she can start applying to government agencies for assistance.

And so now the complexities begin. Existing email addresses and telephone numbers are often the very tools used by these agencies to verify the identity of an applicant. If they have just smashed their phone into small pieces this may represent a significant challenge.

Even without exploring the legal requirements regarding consent of a spouse before some details can be accessed and changed, or a partner can be excluded, the situation is riddled with the anomaly we commonly call a Catch 22. You cannot log into your record without the mobile phone that you wish to report as no longer available. Changing these details at the offices of various agencies may be the only means possible. That relies on having original documents that may well be in the filing cabinet in the family home where an angry spouse sits armed and waiting for the opportunity to punish the person fleeing the control and abuse to which they have been subject for years.

Without getting into the tangled web that faces every victim of domestic violence it is apparent that anyone outside what is considered the standard digital capacity of the modern citizen faces the traps and pitfalls of those systems once the cracks open up because one piece of the puzzle is missing.

The My Health record is a recent example of a controversial system that we are assured is perfectly easy to control, simply by logging in and specifying how we want it managed. The assumption, again, is that we all have access to our record online.

Does it matter?

To test how dependent you are on your online connection, try leaving your phone at home and going through a normal day. Turn off your domestic wifi and see how well you can meet the demands of your family. Watch the people landing at an international airport. They will queue for half an hour to get access to WiFi so they can reconnect to the services that locate and verify them.

Reflect on the news stories that emerge when the power is off for more than 24 hours across large sections of a community. The water runs out, fuel pumps stop working, food rots in refrigerators that no longer remain cold, cold, hungry desperate people take advantage of the darkened streets to help themselves to what they need.

We live in a highly integrated and fragile world that relies on all its constituent parts functioning correctly to maintain the lifestyle to which we have become accustomed. Those people who do not have access to all those components work twice as hard to maintain a base level of engagement. The exclusion of these people from our online activity is a major disempowerment and disadvantage for a whole class of people that is largely invisible to those of us who never experience it.

It is the assertion of this article that we need to address this imbalance by supporting the digitally challenged as an integral part of our social safety net.

It is a topic of further exploration that their inability to engage removes any degree of control over how they occupy that digital world. The irony of that situation that may seem abstract and of little interest but it actually identifies a major challenge. The digital representation of ourselves now occupies an important place in the global systems by which we define ourselves that is rapidly becoming more significant than the physical self. We have already forgotten that not so long ago, the physical self completely defined us.

But that is a consideration for another article.