Decoding ‘orphan crop’ genomes could save millions of lives in Africa

Howard-Yana Shapiro, a scientist with the Mars confectionery company, will make the information free to boost harvests

-

John Vidal and Mark Tran

- The Observer, Sunday 2 June 2013

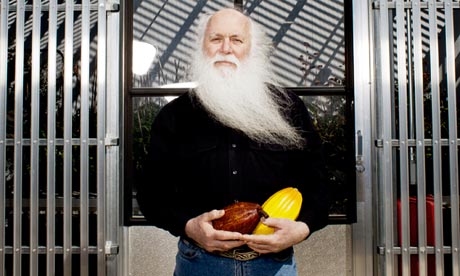

The future wellbeing of millions of Africans may rest in the unlikely hands of a vegan hippy scientist working for a sweet company who plans to map and then give away the genetic data of 100 traditional crops.

Howard-Yana Shapiro, the agriculture director of the $36bn US confectionery corporation Mars, led a partnership that sequenced and then published in 2010 the complete genome of the cacao tree from which chocolate is derived. He plans to work with American and Chinese scientists to sequence and make publicly available the genetic makeup of a host of crops such as yam, finger millet, tef, groundnut, cassava and sweet potato.

Dubbed “orphan crops” because they have been ignored by scientists, seed companies and governments, they are staples for up to 250 million smallholder African farmers who depend on them for food security, nutrition and income. However, they are considered of little economic interest to large seed and chemical companies such as Monsanto, Bayer and Syngenta, which concentrate on global crops such as maize, rice and soya.

According to Shapiro, there is huge potential to develop more resilient and higher-yielding varieties of most orphan crops by combining traditional plant breeding methods with new biotech tools such as “genetic marking”. This does not involve the altering or insertion of genes that takes place with controversial genetic modification.

“The genetic information will be put on the web and offered free to plant breeders, seed companies and farmers on condition it is not patented. A new African plant-breeding academy will also be set up in Nairobi, Kenya,” he said.

“It’s not charity. It’s a gift. Its an improvement of African agriculture. These crops will never be worked on by the big five [seed] companies. They don’t see them as competition.”

Shapiro, a leading plant scientist who founded organic seed company Seeds of Change but sold it to Mars in 1997, now cuts an idiosyncratic figure in the corporate food world, sporting a long beard and listing motorcycles as a favourite pastime. But he said that the culture of the family-owned corporation had advantages. “It took less than a nanosecond to decide not to patent. Ownership was not an issue,” he said.

Shapiro is angered by the stunting caused by malnutrition that affects 30% of African children. By improving the crops, he said, the African orphan crop consortium, which includes corporations such as Life Technologies and the conservation group WWF, could eradicate a “plague” that costs Africa $125bn a year. “We will start with genomics, go to analysis, then to plant breeders, then to the field, then the seed companies, and then to the farms,” he said.

Open-access publication of the cacao genome in 2010 is now bearing fruit. The genes that determine resistance to fungal infections and yield have been found and a new generation of cacao trees is being grown which should eventually quadruple production. “We haven’t changed a single gene. It’s inheritability. It’s all done with grafting.”

But the “improved” seeds expected to come out of the $40m orphan programme could change Africa in unexpected ways. Nearly 80% of all seed used in Africa is selected, saved and exchanged by farmers without money changing hands. The result has been an immense diversity of crops suited to particular localities and cultures. The new, “improved” seeds of the orphan crops may increase yields or disease resistance but could be unaffordable and might oust traditional varieties. It is also possible that the genetic decoding could open the door to genetic modification.

Yam harvests could increase significantly as hardier varieties are developed.”Anything that keeps the [genetic] information out of proprietary hands is a good thing. But it’s important to maintain the traditional varieties that have not been ‘improved’ and to keep a non-monetised path for the farming economy,” said Camilla Toulmin, director of the International Institute for Environment and Development in London. “It’s important to recognise improvements in crops are not just about genetics. How plants are managed is equally important.”

Yam harvests could increase significantly as hardier varieties are developed.”Anything that keeps the [genetic] information out of proprietary hands is a good thing. But it’s important to maintain the traditional varieties that have not been ‘improved’ and to keep a non-monetised path for the farming economy,” said Camilla Toulmin, director of the International Institute for Environment and Development in London. “It’s important to recognise improvements in crops are not just about genetics. How plants are managed is equally important.”

Agricultural investment in Africa will be a key point at the G8 hunger summit in Northern Ireland next weekend. Governments and 45 of the largest agribusiness corporations are expected to unveil initiatives to boost African farming.

West and east African small farmers’ groups have joined British charities to say that small-scale family farmers were being excluded from the talks even though they feed 80% of Africans. “It’s very important that governments prioritise investment to support family farmers and their more ecological food production,” said Patrick Mulvany, chair of the UK Food group.

“Technological advances in food production can be part of the solution to increase yields. But the world already grows enough food yet one in eight people go hungry every day. G8 leaders can begin to tackle the scandal of global hunger by closing the tax loopholes, improving land rights and increasing public investment in developing country agriculture,” said Lucy Brinicombe, spokesperson for the If coalition of 200 groups which includes Oxfam and ActionAid.