Hansen et al. 2012

A recent paper in PNAS by Hansen et al. (there’s also a recently releaseddiscussion paper on the topic) has caused quite a stir. The essential result is that extreme heat (beyond the 2-sigma and even 3-sigma level) has become so much more commonplace, that the only plausible explanation is global warming.

In a sense, this paper doesn’t tell us much we didn’t already know. What it does accomplish is to show in practical terms the observable result of man-made global warming, which is not just to make the average temperature hotter, but to make extreme heat so much more common. What was once 3-sigma heat — which at any given time we would expect to cover less than 1% of the globe — is now at least 10 times more prevalent. There have been 3-sigma events before, it’s true, and because of that we know that such extremes have consequences. When they’re as rare as they should be, life can recover from those consequences. When they’re 10 times more common …

I have two criticisms of this paper. First, the exposition is not always as clear as it could be — but that’s a matter of style more than substance. Second, it gives the impression that variability of temperature has increased recently. I’m not convinced that’s the case when considering local temperature because part of the increased variability in “standardized” (i.e., scaled by the local standard deviation) temperature anomaly is due to spatial rather than temporal changes — different amounts of overall warming in different locations (i.e., differenttrends) — as I stated here. I admit I haven’t analyzed hemispheric data, nor did I (in the previous post) consider seasonal (principally summertime) temperature specifically.

But in another sense, temperature variability has increased precisely because of spatial as well as temporal variability. The point of Hansen et al. 2012 is that what used to be rare extreme heat is now much more common. Much. This is made even more true by the fact that some regions have warmed (trend-wise) more than the global or hemispheric average, so they’re even more susceptible to extreme events (“extreme” by the standard prior to 1980).

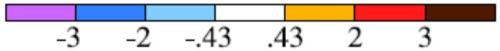

Even hot times in earlier years don’t stack up to what we’re seeing today. In their more recent discussion paper, they show standardized anomalies (i.e., anomalies divided by the local standard deviation) for summertime in the northern hemisphere, using a longer baseline period than in the original paper (in response to some critics). Here’s the color legend (units are standard deviations):

Here’s the map for the very hot summer (in the U.S.) 1936:

Note the strong heating over much of the American midwest, with a small region even showing 3-sigma (or more) heat (dark brown color). It was hot back then in the USA, but only 1% of the northern hemisphere was in the 3-sigma or more extreme range. Now look at what happened in the summer of 2010:

Not only is there a region of 3-sigma heat along the east coast of the USA and another along the north coast of South America, there’s a giant area from Russia down through the middle east. Fully 18% of the hemisphere is in the 3-sigma range. That’s not “natural variation.” It’s global warming.

This is, I believe, an important way to characterize the simple temperature effect of global warming because it puts it in the context of what we’ve seen before, of the conditions on which we have based building our modern civilization. The baseline period for their recent analysis is 1931 to 1980. That’s when we layed out the infrastructure which drives modern high-tech civilization. Those are the conditions from which we derived our expectations. But because of global warming, conditions today exceed expectation much more often than they used to. Much more often than we’re prepared to deal with. Much.

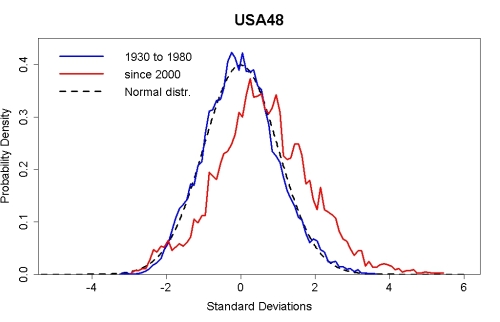

I did a similar analysis for the lower 48 states of the US only, using summertime-mean data for climate divisions from the National Climate Data Center. I compared the distribution of standardized (i.e., scaled by the local standard deviation) temperature anomalies prior to 1980, to those since 2000 (using 1930-1980 as a baseline period):

The most important aspect of this comparison isn’t the higher mean value for the most recent temperatures. It’s the fact that extreme high values — above 2-sigma and especially above 3-sigma — are so much more frequent. Much. And that’s the real problem. When a 3-sigma event happens, it’s a problem but we can deal with it and recover from it. When 10 (or more) times as many 3-sigma events happen … we have a problem.

That means we’re already in trouble. The really bad news is that we’re already in trouble from just the warming we’ve already experienced, but it’s going to get worse because it’s going to get hotter. You think the 2011 Texas-Oklahoma heat wave was bad? You think this year’s corn-belt heat wave was bad? You think the 2010 Russian heat wave was very very bad? You ain’t seen nothin’ yet.

That’s why Hansen et al. is so important. From a purely scientific perspective it doesn’t really add to our knowledge. But from a human perspective, it lays it on the line. We’ve had bad heat events in the past but now they’re so much more common they’re vastly more difficult to deal with, so stop kidding yourselves, it’s already a bad problem and it’s just gonna get worse.

All this reveals the utter foolishness of Cliff Mass’s distorted view that global warming has little to do with the extreme heat witnessed in recent years in many places. His argument is that global warming has raised temperature in the U.S. by about 1 degree F, but last year’s Texas-Oklahoma heat wave was 7 to 8 deg.F over large portions of TX and OK, so global warming is only responsible for a small portion of that heat wave.

Even if his result were correct (which it is not), he utterly misses the point. Rather than sum up the situation the wrong way as he does, Hansen et al. did it right, showing that global warming doesn’t just make heat waves hotter. What’s much much much more important is that it makes heat waves more frequent. Cliff Mass gives the impression that there’s nothing to worry about because our “3-sigma” events — the real killers — will only be one degree hotter, quite ignoring the fact that we’ll get 10 times as many of them.

13 RESPONSES TO HANSEN ET AL. 2012

LEAVE A REPLY

| Alex the Seal on Hansen et al. 2012 | |

| adelady on The Small Picture | |

| adelady on Hansen et al. 2012 | |

| bananastrings on Sea Ice Poll | |

| bananastrings on The Small Picture | |

| Bryan Stairs on Sea Ice Poll | |

| Horatio Algeranon on The Small Picture | |

| Rattus Norvegicus on Hansen et al. 2012 | |

| bananastrings on The Small Picture | |

| Douglas Ricker (@DHR… onHansen et al. 2012 | |

| Michael Sweet on Hansen et al. 2012 | |

| Andy S. on Hansen et al. 2012 | |

| Philippe Chantreau on The Small Picture | |

| Bern on Hansen et al. 2012 | |

| Brian Dodge on Hansen et al. 2012 |

| S | M | T | W | T | F | S |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| « Jul | ||||||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | |||

| 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 |

| 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 |

| 19 | 20 | 21 | 22 | 23 | 24 | 25 |

| 26 | 27 | 28 | 29 | 30 | 31 | |

Shouldn’t we compare timespans of similar lengths? Does that have any influence on the frequency of extreme events?

[Response: The graph shows frequency of occurrence per unit time.]

“Second, it gives the impression that variability of temperature has increased recently. ”

Ah. I had missed your variability post from July 21 (that should teach me not to go on vacation) – I found it very interesting. I encourage you to publicize that result further: I consider myself a climate change professional, yet I had taken the Hansen et al. type graph at face value in terms of showing an increase in variability in addition to the mean, and I think your July 21 post is pretty convincing that this sort of skew would be expected from averaging across a region with differing trends (not that there might not be an increase in variability anyway, only that you have to do a more sophisticated analysis to detect it).

I’m wondering if your USA48 graph could be looked at in another way: the percentage of the country that is likely to be X standard deviations above the local mean? Eg, it isn’t that in any given location in the US, you’re much more likely to see a 3-sigma event…

Also, while I no doubt disagree with Cliff Mass’s conclusions, I do wonder: if we originally have 5 days of 3 degrees above normal, and 1 day of 4 degrees above normal in our base case, which is the better way to portray a 1 degree warming: a 5-fold increase in 4 degree events, or a 1 degree increase in what used to be 3 degree events? The former sounds much more disastrous than the latter, even though they describe the same situation… implying that there’s a subtle issue going on here. Perhaps we need to think about how non-linear the damages are: if there is a threshold, or high non-linearity, then the former (five fold increase) is a better way to think about it, whereas if damages are fairly linear with temperature then the latter (just add 1 degree to any historical temperature) gives an impression closer to reality…

-MMM

Corn pretty much can’t grow (at least the current strains) if the average daily temp is above 86F. That is a distinct non linearity.

MMM, there is a definite non-linearity of damages brought about by the fact that homeotherms have an effective upper temperature above which they cannot survive because they cannot maintain their core body temperature because they cannot cool fast enough. As the environmental temperature approaches that temperature, the percentage reduction in cooling ability increases more with each degree C increase in temperature. Treating the upper temperature limit as 40 degrees C, an increase in temperature of 7.5 C will effectively halve the ability of homeotherms to cool themselves, but it will only take an increase of 3.75 C to halve it again, and 1.875 C to halve it a third time. Clearly I have simplified because humidity is a major factor for cooling for most homeotherms, so wet bulb rather than dry bulb temperature should apply, but the principle stands. This applies not only to humans, who in Western societies can at least find air conditioned locations, but to our live stock as well, who effectively cannot, and to homeotherms in the wild as well, who certainly cannot.

There is an additional non-linearities related to evaporation, and (no doubt) other factors.

What is more, Cliff Mass’s application of his reasoning is simplistic. He provides no evidence that the mean temperature increase during weather events that introduce heat waves is not greater than the mean annual increase. The mean night time, day time, summer and winter increases all differ from the mean annual increase. Given that, he is not entitled to an assumption of uniform temperature increase in assigning effects to either weather or global warming.

the exposition is not always as clear as it could be

Wow, that’s unusual for an academic paper. 🙂

“Much”! ??

As planers and policy makers plan critical infrastructure, they have to plan for much higher temperatures, and that results in much higher costs. And they have to plan for those temperatures arriving much sooner than expected.

There goes all the cost savings from not fighting global warming. Everybody underestimated the costs from global warming. Everybody discounted the costs from global warming too much by placing the damages too far in the future.

Still, if there is a future left to plan for, we are going to need some numbers to use as a basis of planning.

I suggest that we need an estimate of the total heat stress that infrastructure or people or crops or organizations will be exposed to over a continuous period of 10 days. or 20 days. And it is very non-linear. A day in 100F heat is much worse than a day in 90F heat. Three days in 90F heat is much worse than a day in 90F heat. And, if you are going to be in 100F heat for 10 days, you need to stay hydrated. And if you are building infrastructure in those kinds of places, you need to plan for the heat.

If your only basis of planning is, “Much heat!”. Then, about the best you can do is a gravel road, and adobe buildings.

There are also nonlinear responses to high temperatures in plants.http://themidwestcultivator.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/02/Chart-Photosyntesis.jpg.png

Thanks for the article, Tamino. I think those maps of 1936 vs 2010 should be the “final nail in the coffin” of the “but, but, 1936!” denier argument. But I’m sure it wont be…

It’ll be interesting to see what the 2012 map looks like, particularly in the US.

What about sample size effects in your’s and Hansen’s graphs? For example, Is there a 12 year time period between 1930 and 1980 that would produce a similar bell curve shifted to the warm side like in the 2000 to present data? Could there have been similar periods some other time during the Holocene? How do we know for sure how much we’re cooking the earth? Can statistics answer this without the passing of more years and us waiting around until it’s too late to do anything more than wring our hands?

Tamino,

Another good post. It is informing to see your analysis of this paper. Your clear point that the key conclusion is rapidly increasing extreme events is important. I will be interested to see how the analysis of increasing temperature variability goes in the future.

Even more frightening is the appearance of 4 and 5 sigma events. In your graph above for the US, the 4 sigma events are obviously greater than 1% (by eyeball) and 5 sigma is greater than zero. In the period of record both of these were zero. We have not even reached 2C yet, which is the current “target” for no harm. What do you think the farmers in Texas think about 2C?

Thanks for this analysis of Hansen v. Mass. The only part I’d quibble with is this: “But because of global warming, conditions today exceed expectation much more often than they used to. Much more often than we’re prepared to deal with.”

If we could somehow keep the warming to current levels, I think we’d adapt to it reasonably well. As Stuart Staniford pointed out on his blog last year (i.e. before this years drought), global food production has kept increasing despite the Russian, Texas, etc droughts.

But we’re rapidly approaching a point where this will no longer be true, and a lot of it is already “baked into the cake.” Perhaps this will be the year it starts showing up in food production as well. Depressing thought.

Australian farmers are looking forward to higher prices this year on the back of US farming difficulties. Unfortunately we are likely looking at El Nino conditions – Australian agriculture tends to suffer badly:

“Huge US corn and soybean losses just forecast by the US Department of Agriculture are helping drive US wheat prices higher.

Record US corn and soybean prices stemming from drought-ravaged yields and a 12 to 13 per cent drop in forecast production versus last year are driving the sharp wheat rise.”

http://www.abc.net.au/rural/news/content/201208/s3566235.htm

I’m not sure where you are getting your data from.

“If we could somehow keep the warming to current levels, I think we’d adapt to it reasonably well.”

I’m not so sure. All you need to look at is crop failures and successes. The top 5 wheat exporting countries/groups – USA, Australia, Canada, EU, Russian Federation – occasionally have major individual or combined failures. What happens when droughts and/or floods affect 2 or more in the same growing season … in the year following a major failure in just one of them?

And if we’re talking *major* crop failure, you can be pretty sure that the country/ies in question will also fail in one or more similar crops. World reserves of grains are already pretty low. Considering the crop impacts of just Russia 2010 and USA 2012 of extreme weather, we’re literally dicing with death if we think we can keep doing this without running headlong into the statistical inevitability that this climate regime will, sooner or later, allow multiple failures in one growing year.